Part 2: Information, BookTok, and Cultural Selection via The Revolt of the Public

Acts III & IV

If you haven’t read Part 1, you may find it here. New subscribers have the option to use their one free post option for this piece. If you have the ability/desire, please consider a paid-subscription for cultural hot takes, like this piece on your fellow Americans who voted in the last election that helped to generate my first paid subscription (thank you!) and inappropriately equating celebrity with god-like status, like Neil Gaiman and my experience working with one of the top a capela groups in their field at a summer workshop.

Because of how long Part 2 became, there will now be a Part 3, coming the week of March 17.

Who determines cultural value and how do we define it?

You might define culture as a method of status competition among the higher classes, part of their dominance games to determine hierarchy, power, and mate selection. If you’re Roman Catholic, we might define culture as the pinnacle of art that inspires us to the true, the good, the beautiful—essentially, that which inspires us to look to God and elevate our minds. Culture might be that element that acts as the connective tissue, the substrate that lends rich, deep meaning to a people, time, and place that demarks the passage of time and important events in history.

might say that it is the elements of taste of those who represent the elites of our society through the hierarchical stratification of information that trickles down to the masses, who, according to him, do not necessarily reflect the interests of “the Public”.Postmodernism,1 like the iPhone to the film camera, broke apart the consensus understanding of art—certainly those rules that governed which attitudes were “correct” in selecting works to preserve, display, and fund through patronage to artists; these patronage systems do still exist, but they generally are not in the interest of the masses as a whole, especially the lower classes, which I hope to explain through the course of this essay. The issue of postmodernism at its core, is that all knowledge is subjective, according to the whims of the moment. Art and culture can mean anything you desire it to, because no one can tell you what it means to you. This is a fallacious argument, because it doesn’t allow anyone to criticize or better yet, create a measurement to judge how good or well-done a piece is. If there is no yardstick, anything can be of value. We can no longer determine if the skill being used has improved or worsened with time.

Let’s put it a different way:

For the professional (writer, musician, artist, athlete) who can produce a given product or result over time, there is but one way to really measure performance and growth: competing with yourself.

Present-day capitalism, through the methods of industrialization and “scientific management” (think Frederick Winslow Taylor, the man who inspired Henry Ford and his sophisticated, streamlined but impersonal, dehumanizing system of the assembly-line) has melded with the Marxist view that the interests of the masses trump the individual; paradoxically, American culture (see The Culture of Narcissism) deifies the individual at the same time. Present social culture is an inheritor of these disparate ideas now rarified through the hyperreality lens of social media’s impact on individualism, on extreme display against everyone else, also competing for the limited attention span and dollars of their consumers. But this competition is false information to self-esteem and self-worth, as well as the worth of the individual within American society. True competency lies not in competing with others; at a certain point, for anyone who expends the effort, we attain enough competency to be relatively well-matched with our competitors (this is particularly true in sports where brute strength, skill, and strategy are all key in winning a match). For the creative, it is not as much about competition with others in skill or creativity, but in competition with our past selves.

If you started drawing a year ago today and were only capable of drawing a stick figure, and you kept at it each day, learning form, structure, how to break figures and elements into their base shapes, with or without natural aptitude, you would learn at some point how to draw in your own style. It might not be Fr. Angelico, Winslow Homer, or Georgia O’Keefe—all very different styles of artists. But it would be yours, and you would have a point of reference over the course of every day for a year to determine how your skill had grown. You have a record. You have a baseline yardstick by which to measure your art—a set of established standards for comparison.

In a similar way, we have a record over time of not only the kind of art that has been produced, but for as long as some level of a hard copy exists in multiple places, we have a record of how art, the opinions of philosophy, and art/cultural critique have changed and been shaped over the last century of the postmodern era.

Part 1 dealt with two ideas:

Ideological capture of the higher learning institutions

Gatekeeping and networking nepotism among the elite classes within academia and higher social strata of those with the right attitudes and beliefs to determine what counts as culturally relevant and what doesn’t.

I suppose those who followed last time are wondering what this has to do with Romantasy (the Romance and Fantasy genre rolled into one), BookTok, and Martin Gurri.

Well …

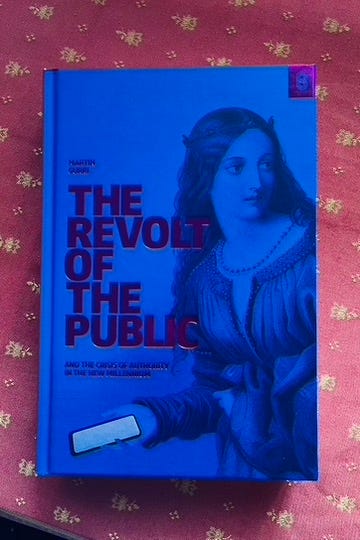

Act III: The Revolt of the Public and the democratization of Information (Culture), according to Martin Gurri (at least, what I think he might posit)

was a CIA analyst who self-published a book rather quietly in 2014. Over the next decade, the book gained traction, especially, I presume, after the election of Donald Trump. As others who credit and cite Gurri attest, he predicted the rise of our current president.

Gurri’s assessment of the conditions that lead to the election of Trump are correct; Trump is a populist—he’s not a true through-and-through Conservative or Democrat, if you ask anyone who’s been a member of either party, or the middle even, with serious detached reflection and assessment of his positions through his live. What is most interesting about Gurri’s theory are how the conditions and mechanics of the current information dissemination system destroyed the previous methods and avenues that dictated how the system worked. We, the masses and “the Public” have been changed and are only dimly aware of the shift. “The Elites” are still so badly out of touch that they fail to understand that the means and methods of information dissemination and control have changed irrevocably. They seem to be unaware there has been a change at all, cannot fathom how they lost control, and have no idea how to reign it in.

We can see this through the lack of understanding how to utilize this new system to generate interest in new products by big publishers. That fact is, however, that it is impossible to predict and is as capricious and subject to change as storm winds.

Gurri calls the invention of the internet “the Fifth Wave”, as the printing press was the Fourth Wave, after writing in general and a couple other inventions for information conveyance. He isn’t wrong. About 200 million businesses use Facebook,2 and nearly half the world’s population uses the platform.3 Those facts alone are staggering, in their numbers and the fact that half the world’s population is using the same product every day. Gurri’s theory is complicated and the written part of the book is about 350 pages. Not to badly oversimplify, but for brevity’s sake, here’s the quick and the dirty of how information was roughly disseminated and its relationship to how “The Revolt of the Public” works.

Information was a top-down endeavor by those in power: who had the most money, crops, clout, connections, strength, livestock, etc—whatever the currency or standard was. As societies became more sophisticated, those status items that determined wealth, prestige, influence, and control evolved and shifted. People who had the ability to read and write could influence thought the most. If it can be recorded, it can be studied and kept track of, according to whomever the victor was.

Writing and learning were an expensive and complicated skill to learn. They took time. In the West (which is where and what I’m familiar with and can speak to), the Catholic Church (later split as Roman, Orthodox, and Protestant denominations) was the greatest proliferator of written and recorded knowledge. Information was kept first on scrolls, and members of the religious or advisory class spent thousands of hours, across the span of their lives, hand-copying books, treatises, and the latin Bible. Paper broke down over time and ink faded, and paper wasn’t necessarily cheap to produce. It also, like everything else during the Medieval era, took considerable time, effort, and resources to create. Automation and industrialization wouldn’t occur for hundreds of years, until the 1800s.

Nobility could be educated, but it was not common for royals to be able to read. Some could. But primarily, education was available through the religious class or hiring a private tutor, not an option for most of the people’s of Europe. Literacy was not widespread.

This meant dedication in service to the church through religious life as the most common means of access to learning to read, but it also meant freedom from too much poverty, a roof over one’s head, and often a place for men who weren’t going to inherit because they had elder brothers (as the joke goes in The Name of the Rose), and for women who could pursue freedom from unhappy marriages through a life of voluntary poverty and service to the church. It was a better deal than living a life as a serf (indentured slave) to a piece of land owned by a lord, getting killed, or being married to someone potentially odious or unpleasant as political advantage to one’s family.The invention of the printing press revolutionized the written word. It allowed the proliferation of information by anyone who could pay to have something printed sent out into the towns and disseminated to a wider population of literate individuals than just those few who had been educated by the religious class, or by access to the private libraries of monasteries and abbeys.

Over time, large sprawling institutions have sprung up in our societies that are hierarchical, sometimes bloated, and vast. As those that stayed in the elite class or rose up to the level of the elite class, information was disseminated in a top-down way. Prime, easy examples that come to mind: the coverup of President Woodrow Wilson’s stroke and the strong likelihood that his wife was running the country in his last year to year-and-a-half of life; the coverup of President D. Roosevelt’s being in a wheelchair through pretty much all of his presidency; the multitude of affairs and pain medication addiction of President JFK; President Ronald Reagan’s slowly unfolding dementia in the last term of his presidency. All these examples do deal with presidents, but the information would have been damning to their public image and election or re-election had it be known at the time of its occurrence. If you were the voting public, would you want the unelected wife of your politician, whom you gave your trust and your vote, calling the shots? If you behaved in ways that those elites in circles of government or culture disapproved of, one might up with unpleasant consequences. We might turn to the example of Jean Sebring, the actress whom J. Edgar Hoover actively pursued with his position and resources to torment and harass her for her political affiliation and involvement supporting the Black Panthers (whether you like her politics or not). Sebring, tragically, first miscarried her child after receiving threatening phone calls and harassment that upset her mental condition, and later, committed suicide after the harassment escalated.

These sprawling institutions and those appointed to positions of authority and power kept this information quiet; such information would discredit the administration at the time, cause chaos, and disrupt the whirring of government systems. Through nepotism and networking, the right person would suck up to so-and-so and get their appointment. Through traveling in the right circles, one would have access to those who could be king-makers and the connective glue to the arts, politics, and upper social strata. Such systems and circles still exist, and will continue to exist. But the rules have changed.

The internet upended the old system.

Gurri makes the case by detailing the Arab Spring uprising that took place in Egypt in 2011; I am assuming, he still worked at the CIA at the time and had ample access to the systems of information that allowed him to survey world events and draw information to reach his conclusions. An incident of a man self-immolating after harassment and intimidation by the then-government sparked heated anger and resentment among a chunk of the population who had access to social media. The outrage was caused because there was visual evidence of the man setting himself on fire; a few months prior, a similar self-immolation case had drawn little attention, and Gurri concludes, because there was no video to accompany the death. An Egyptian techie started an open Facebook event inviting people to open protest, which drew thousands of people in real life, and my guess, thousands to hundreds of thousands of impressions. The video of the self-immolating man drew international attention. Due to pressure from the Public, and efforts by the Egyptian military, who were against the Muslim Brotherhood-backed president, the then-president stepped down as the military took over.

Information, as I had said before and explained, had generally been top-down and in the hands of those in control of the reigns of information. We might use the concept of gate-keeping theory (from mass communications) to understand the nature of information we face. Information on the internet, good, bad, fact and opinion, is not simply a flood. It is 500-foot tsunami, compared to the pond of information our ancestors had access to, dipping our toe in periodically. A news bureau or other media company is a mediator to sift through the information for us and determine what is relevant and what is irrelevant. The fact is, there is more information that can be consumed consciously at any one point by a mind. This is why we need sources of authority that we trust to help us make sense of the vast swathes of data and information available to navigate our reality and determine what is relevant and important to ordering our lives. Otherwise, a flood is a flood; we drown in it and struggle to understand and make sense of what we experience.

It doesn’t help us to know what clandestine operations the CIA or NSA is carrying out; most of that intelligence gathering and espionage work isn’t going to impact the cost of eggs. However, the internet, being the tidal flood that it is, threatens government, media, and business gatekeepers. Gurri’s point is that the internet democratizes all information; there is no need for a gatekeeper to tell you what to think about and how to think about it. If you can’t find it free here, you can find it free somewhere else, and there is often someone to provide an alternative or counter view to the narrative you’re being told through whatever mainstream media outlet you source your information from. You are a free information citizen; you don’t need a mediator as much as you once did.

It is a threat to the current powers that be that are in control of liberal democracy. It delegitimizes the authority and power of those who are in control of the information flow by allowing people from all social strata to communicate across oceans in real time, and challenge what they read from the gatekeepers with the views of other people.

Because of the ability to corroborate one’s experience to others via real-life conversations as well as online (though we do take a grain for salt for what random strangers are saying elsewhere), we can patch together a another narrative. Sometimes, it is closer to the truth; sometimes not. Regardless, the arbiters of information and culture have lost the ability to tell us what we can and should buy because they said so.

Act IV: BookTok, or how Culture flows from the bottom up

In my previous post, I discussed that in many parts of modern society, much is still a meritocracy. J.K. Rowling became unbelievably successful, despite not having patronage or the right connections to get her book noticed, to go on and become a billionaire. The same could be said of Stephen King, who used to work as a janitor. These were not rags to riches overnight; both they and countless other examples of creatives built a strong foundation in practicing their craft, working at it, and putting in their blood and sweat to make the “dream” a reality.

But not all books on the New York Times bestsellers list get there because of their merit. Often, as

at noted in his article about Barnes & Nobles’ turn around, publishers push a book with a promotional monetary incentive to bookstores: buy lots of X book and advertise it everywhere in the store:Leaked emails show ridiculous deals. Publishers give discounts and thousands of dollars in marketing support, but the store must buy a boatload of copies—even if the book sucks and demand is weak—and push them as aggressively as possible.

Publishers do this in order to force-feed a book on to the bestseller list, using the brute force of marketing money to drive sales. If you flog that bad boy ruthlessly enough, it might compensate for the inferiority of the book itself.

Many of the books that we see on the shelves are “classics” or books that are part of a series, previous items by authors who sell well, celebrity books (often with ghostwriters) and yes, books that are being pushed because the publisher and whomever they’ve employed to market and push these books, have determined has relevance. When we consider it, there’s an enormous amount riding on the titles publishers put out: all the time, money, and manpower spent, as well as the concern for their bottom line that the book do well enough to earn back and justify the expenditure of all of those resources. I know to an extent because I contracted as a proofreader reading the final proof in the last round of editing for a major publisher.

If information has now been democratized, to the point that a single person on social media can cause disruption by organizing a protest, that works off of algorithms, and snowballs into a larger demonstration or catalyst for a movement,

what are the implications for culture as it appeals to the masses, to the curation of culture, and the marketing vultures and parasites seeking to profit from the tidal change?

This is where BookTok comes in.

(@sincerelymaariya) over at Musings sums it up nicely:In walks the rise of BookTok, the rise of a new set of criteria drawn up mercilessly by teenagers, heralding a whirlwind of new literature, new genres, and discarding the old. Personalities are based off of characters, looking to the famous bookworms that litter our culture - Hermione Granger, Rory Gilmore, Elizabeth Bennet, Matilda. Reading is cool, reading is fun, reading is sexy. …

It isn’t its popularity that irritates me, it’s the twisting of criteria. Suddenly, all genres have taken on a new meaning - most notably Romance. No longer is it the demure flash of an ankle, the bashful skin-to-skin hand holding, lingering glances and forbidden meetings (Mr Darcy, the main perpetrator). There has risen a new need and craving for graphic romance, so strong in fact, that TikTok deems a book unworthy of your time - unless it includes what is christened ‘smut’. These graphic, well-described, often borderline abusive and definitely not U-rated scenes are all the rage.

I eschew the platform, so for most of the last five years, I haven’t been paying attention to it. I didn’t know what it was till I ran across

post on the stalking and harassment behaviors of BookTok creators when a woman dared to question the rise in smutty romance novels using cartoon-like covers in their marketing as a potentially inappropriate attractant to children. Because I culturally noped myself out, I was unaware of BookTok, its impact on the “reading” public, and the repercussions for markets and market trends.4… the hashtag #BookTok had around 30 billion views. This month that figure is more than 82 billion. “The growth has been astronomical,” Routledge said – and that translates into sales. In the UK, books that used “TikTok” or “BookTok” in their sales keywords collectively sold 2.2 million copies in the first four months of 2022.

BookTok is circular, like most social media echo chambers. There are myriad different types of users—some just want to be exposed to new reads, others enjoy the content to be entertained, or like the juicy publishing drama or catty fights between authors and creatives. But there is an incentive to all social media: attention. Curators and creators are in a constant competition to one-up each other, like journalists and beat reporters of old getting the scoop on a juicy story before their competitors beat them to deadline.

Information and culture is no longer democratized or top-down by the political, government, or cultural elites. It is now made by the chaotic and unpredictable nature of the tastes of the everyday citizen, who is an amalgamation of every piece of visual and auditory media, as well as personal everyday experiences, they have ever consumed.

As The New Statesmen article attests, people use BookTok influencers as authorities and curators, reviewing and promoting books that appeal to their fanbase, helping people to navigate hundreds of thousands of titles across the past and present:

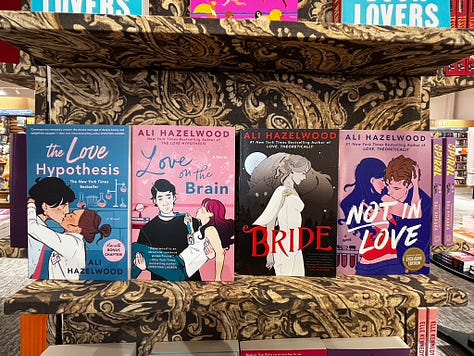

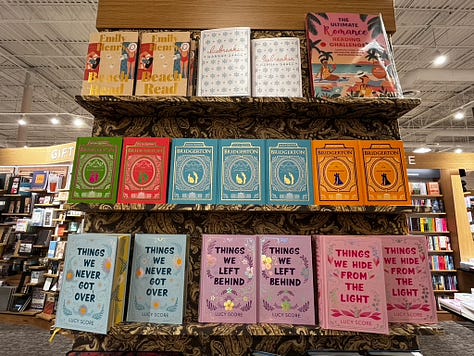

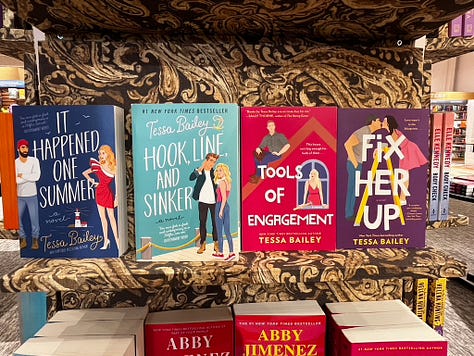

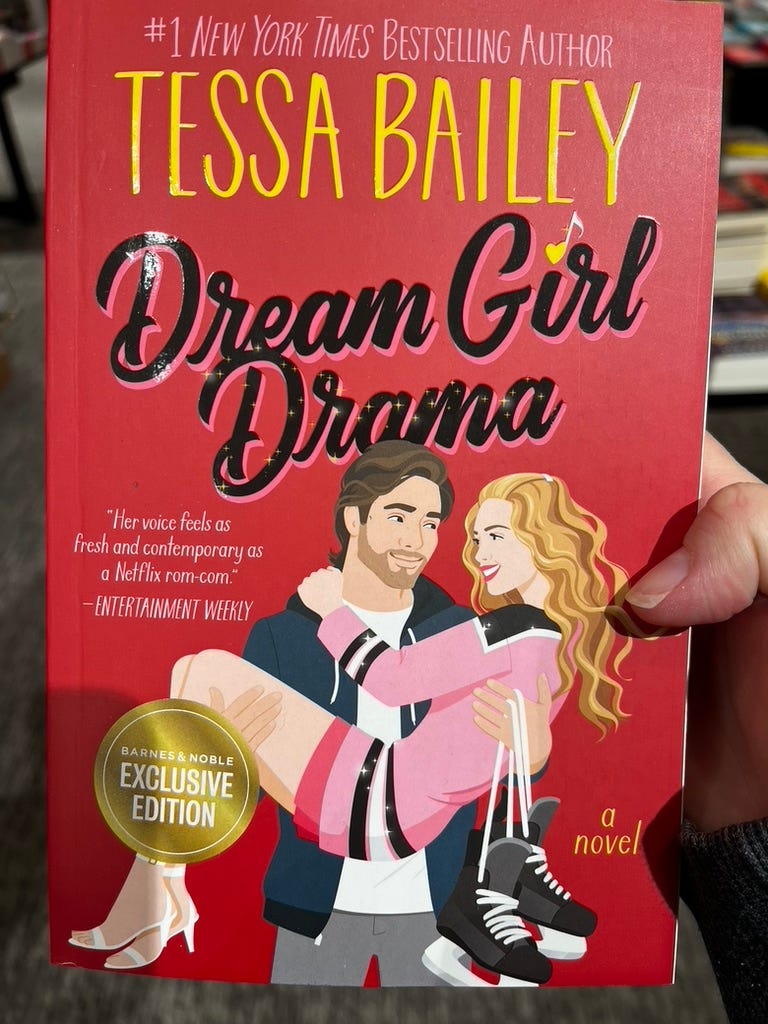

The Fourth Wing, The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo, It Ends With Us, It Starts With Us, Ice Planet Barbarians, The Love Hypothesis, Court of Thorns and Roses.

It just goes on.

The trend seems to go something like this:

A reviewer (influencer) with a platform, reviews the title. Perhaps they do a dramatic reading, act in character, do a product reveal, capture video of themselves ugly crying at the end, or some other performative act as a marketing ploy, to gin up viewership and promote this work. You are entertained and seek out the book, to capture some of the experience promised and the allure of a new title, from your favorite BookToker.

From the New Statesmen:5

While the BookTok phenomenon – and the platform as a whole – grew significantly during the first months of the Covid-19 pandemic, the impact of the trend on the industry is still being felt more than two years later. Its influence is evident even offline: lots of bookshops now curate display tables according to what’s most popular on the app, usually commercial romance, thriller and young adult (YA) novels.

James Daunt, discussed in

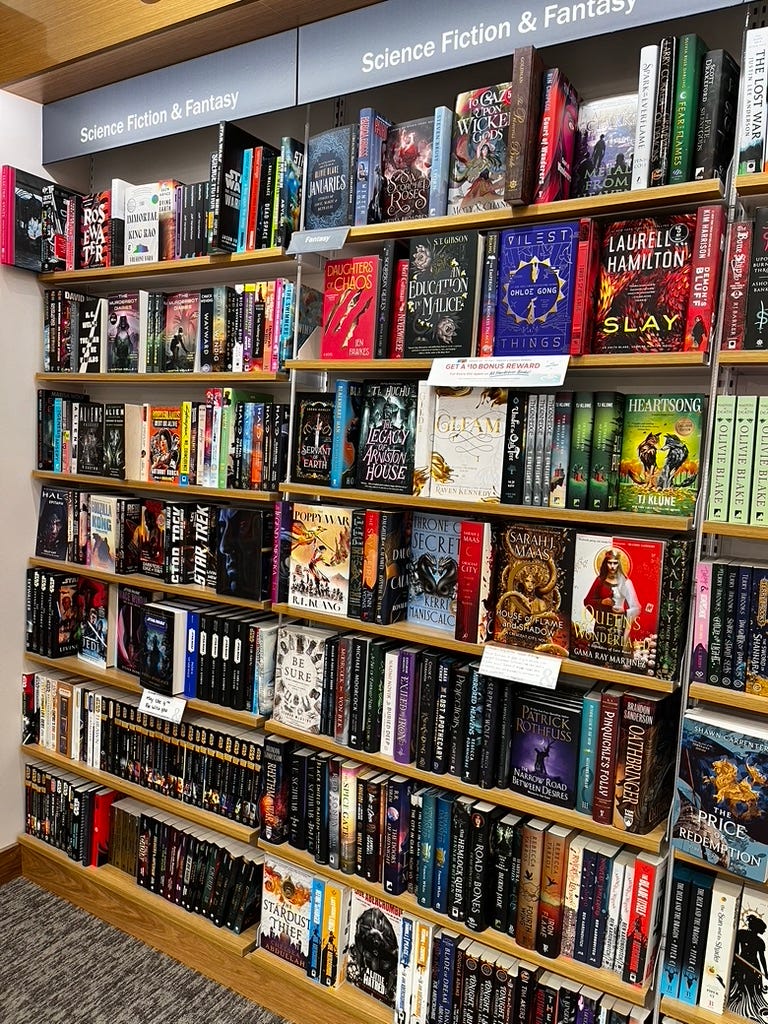

’s piece, had successfully turned around Waterstones book stores in the UK with his model: allow bookstores to essentially choose and curate their reads to appeal to the tastes of their customers. Due to that strategy, B&N was able to turn around in a few years what had been the assured death-rattle of the once great retail chain.But bearing this new method of choosing fiction, at least my local bookstore, has been stocking what has been popular via BookTok selections for their main displays. While the system is no longer the same, the booksellers are still following trends, although they are trends that appeal to the masses, rather than the literary crowd.

Again the New Statesmen:6

Sharma is sceptical of the extent to which the publishing industry is taking its cue from what’s trending online. She has previously advised publishing companies on diversity, and believes the current focus on TikTok is distracting that issue. “Five years ago, there was a push for diversity, equity and inclusion in the publishing industry. No one is talking about that now. Their main focus right now is chasing the dollars that are coming out of social media platforms and content creators who are pushing big books.”

…

Despite the popularity of certain genres and tropes on BookTok, future hits are still difficult to predict. Publishers monitor the platform closely; some even have their own accounts. But “the minute publishing truly infiltrates BookTok, it ruins it”, Crawford said. If publishers and authors – rather than readers – were to take over the platform, “it would ruin that authenticity and the reason people trust BookTok recommendations.”

The information deluge, expanded by social media and the darlings who wield the tool well, forces us to find people who can sift through the flotsam and hold aloft their scavenged finds. While the books of BookTok are not necessarily being pushed by the publishers for thousands of dollars of marketing, materials, and incentive the same way they did with book publishers, that doesn’t mean the books being pushed don’t suffer from the same issue

noted: its held aloft regardless of how good it is or the skill it’s written with. The novels that make it on BookTok are overnight sensations; just ask Colleen Hoover, who has become a millionaire and had her book “It Ends With Us” recently adapted into a feature film with Blake Lively, further spurred into the spotlight for the drama of the he-said-she-said scandal of inappropriate conduct of both the male and female leads toward one another. It’s the kind of juicy tabloid grab perfect for the news-as-entertainment spectacle social media gravitates toward and perpetuates.All markets may not be impacted in the same way that books and literature has benefitted from the visual nature of the social media platform, with video and high and low end graphics, a particular specialty of TikTok. BookTok democratized culture-making books, not through the merit of how well-written the story is, as Musings clearly described the trend toward smut being an all-out requisite to garner the most attention, especially for the blend of romance and fantasy titles Barnes & Noble seems to be awash in for their front displays. The publishers are striving to keep up; rather than continuing to seek new voices that do tell a good story or a different one, they’re following the wave of what is selling, regardless of quality.

It’s capitalizing on what is going to make their bottom line most profitable.

And in the end, we the reader, suffers.

Thank you for reading! Before you go, tap that heart button to show you liked it, share, subscribe, or re-stack this piece! Every little bit helps.

~~~~

a late-20th-century style and concept in the arts, architecture, and criticism that represents a departure from modernism and has at its heart a general distrust of grand theories and ideologies as well as a problematical relationship with any notion of “art.”. Source

Mark Zuckerberg on a recent podcast interview.

The New Statesmen, How BookTok is Changing Literature, 22 October 2022

Ibid

Ibid

Thank you so much for including my article! This is an incredible essay and definitely an important topic that needs to be dealt with a little more. -Maariya